Extraordinary Dwellings

People don’t just live in a house. From trenches to nuclear submarines, from tin cities to space stations; the range of vehicles, products, buildings, and structures is however not infinite, albeit very wide. Categories are needed to present them, but it is more appropriate to organize them by activity rather than materials, shapes, or sizes. This is what the eight groups in this Habitatio chapter attempt to do.

Extraordinary dwellings are those places of residence that are most difficult to define. This section contains everything which falls neither in the traditional categories of urban architecture (single-family homes, low rise high-density housing, and multi-dwelling buildings) nor within the scope of contemporary experimental architecture or folk or vernacular residential architecture.

This study presents extraordinary dwellings in two main sections with several sub-headings. In the TYPES section dwellings are sorted into categories according to the living conditions and roles of the inhabitants. In the ORGANIZATION section, various aspects of the dwellings are illustrated by typical (well-known and common) examples followed by very different examples of extraordinary (rare and extreme) dwellings.

Forty examples accompany the chapter on extraordinary dwellings. The main criterion when selecting them was that they not be the most well-known examples, but ones that are unique, novel and extraordinary in as many ways as possible.

© Elisabeth Toll / source: treehotel.se

TYPES

Places of residence may be classified on the basis of size, shape, structure, (im)permanence, or perhaps the materials used in their construction or many other factors. All of these groupings are valid, or at least theoretical grounds can be found to justify them. The following typology takes activity as its starting point. Who does what in these dwellings? Which social group was the accommodation built for, and what activity did that group do?

Sorting by activity reveals that similar design solutions may occur in several different contexts, as with tents for instance, which may be inhabited by tourists, political refugees, survivors of disasters, soldiers, or polar explorers—although these tents are clearly not all exactly the same. It was also considered important that despite such similarities none of the various types of tent, cabin, vehicle, and other dwellings be omitted.

The order in which the eight groups appear is not accidental. The first group of dwellings faces the worst conditions, those which prevail during wartime, including the most vulnerable of these, when nothing, or rather no type of structure, can ensure the survival of its residents. The next two sections deal with the survival of the poorest people and accommodation for socially deprived citizens. The following three groups cover special accommodation used in everyday life, including stationary and mobile dwellings for religious, work, study, sport and recreation purposes. Then there is a section on travel which includes vehicles with sleeping quarters. Finally in the last group are experimental living spaces.

As the material is extensive and wide-ranging the 40 examples are complemented by web links (to Wikipedia and the websites of manufacturers and professional organizations) to help to orient the reader. The vast majority of the links are to sites in English.

In every war, there are situations where people have no protection at all. This cannot be sustained in the long term, as sleep-deprived, exhausted soldiers become ill and unfit to fight. Often a sheet of tarpaulin is enough to allow sleep, and modern sleeping bags may even take the place of tents. ![]()

![]()

During the First World War, a considerable proportion of the troops fought and lived in 3-4 metre deep trenches of various widths. The British army built 9600 kilometers of trenches on the Western Front alone, which was quite typical. Troops normally spent between one day and two weeks in one place, but there were occasions when soldiers had to spend up to 53 days on the front line at a time. In most of trenches there was no protection from rain and snow, with only some German types of trench having covered areas to shelter under.![]()

![]()

Military camps have been made up of tents since ancient times, which are supplemented nowadays by shipping containers and other prefabricated structures. Camps are usually surrounded by mobile fortified walls.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In the Second World War, both sides built large numbers of bunkers. These were concrete structures, with walls several feet thick, some of which served as barracks and hospitals, not only gun emplacements. ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In the Cold War-era, nuclear bunkers were constructed in many European countries, typically for national leaders to ensure that their countries could be governed in the event of a nuclear strike. These installations had independently functioning air-filtration systems, electricity supplies, communications, and medical and security facilities.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In the lead up to the Second World War air-raid shelters were built beneath new residential buildings. In most cities, it was these shelters that protected the civilian population from bombing raids, although in some cities—London, for example—some civilians sought refuge in Underground stations. This idea spread, and also gave the inhabitants of Budapest a better chance of survival. ![]()

![]()

example: R639

© GYGES / source: gyges.dk

The living quarters in military (and police or civil defense) barracks are typically organized along the same lines as the various military units they house. It is quite common for a dormitory to accommodate a platoon (30 men or more) or perhaps a section (of about 10). Often a whole company (of 100 or more troops) live on one story of a building with shared shower blocks and toilets. The soldiers generally eat in a separate building.![]()

Military (and police or civil defence) training centers either follow the same pattern as barracks or are composed of similar mobile accommodation to military camps, while peacekeepers are usually based in camps.![]()

![]()

![]()

example: Al Asad Airbase

© Torbjørn Kjosvold / source: forsvaret.no

Detention in prisons and prison camps

In prisons, it is typical for the inmates to do all their various activities (eating, sleeping, grooming, toilet) in one space, and this holds true whether the inmates are in solitary confinement, regular cells, or mass dormitory accommodation (with up to 300-400 prisoners together). There are also prisons that are radically different in conception, and these resemble apartments or student accommodation, where everything works along the same lines as in civilian life, apart from the freedom of movement.![]()

![]()

Forced labour camps are normally built by the prisoners, so most of them are composed of simple, wooden barracks. The buildings may be single-span or multiple-span, with most of the interior occupied by beds, which are also made of wood.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Forced labour camps have existed since ancient times, as have organised attempts at genocide, but extermination camps only date from the Second World War, with the exception of the Shark island camp set up in 1904 to eradicate the Herero tribe in south-western Africa. The death camps were similar to labour camps in layout, the difference lies in their mode of operation—the amount of work and food allotted to the inmates was deliberately set at a level that would kill them, in a planned and systematic manner.![]()

![]()

![]()

Prisoner of War camps in the First and Second World Wars were generally similar to labour camps, but the circumstances dictated what kind of accommodation was built or what existing buildings were used. There were also occasions when there was no accommodation for prisoners of war for extended periods. The prisoners might or might not be put to work, depending on the work that needed doing.![]()

![]()

examples: Kwan-li-so No.15, Halden fengsel

© Trond Isaksen / source: openbuildings.com

People become homeless for numerous different reasons: divorce, expulsion from state institutions, imprisonment, illness, alcoholism, drug addiction, mental health problems, unemployment, longterm poverty, and various combinations of these. More than two-thirds of the homeless are men with an average age of around 40, and their death rate is about ten times that of the rest of the population. A third of the homeless live in public spaces, some of which are sheltered in some way from the elements (underpasses, in the lee of buildings, close to ventilation gratings) while the rest live in makeshift shelters on or in deserted properties.![]()

In 2005 a billion people, one in five of the total population, lived in shantytowns, and this ratio has not changed appreciably since. These settlements spring up—illegally and unplanned—in the least valuable areas around big cities. The cheapest building materials are used: corrugated metal sheeting, plastic, and various types of wooden (-based) boards. Drinking water, sewage, and electrical supplies are often completely absent. ![]()

![]()

An example of dwellings which are a step up from shantytowns, but below the standards of normal accommodation are the Favelas of Brazil. 6% of the population lives in settlements of this kind, more than the population of Hungary. Two-thirds of the houses have sewage provision, 90 percent of them have running water and almost all have electric current, and they even have waste disposal services. Although the buildings are usually made of brick and concrete they are very often unfinished, unrendered, and of a low technical and aesthetical standard.![]()

![]()

Slums can also arise when an area of a city that was originally built to a high or at least average standard deteriorates over time. This can be caused by a lack of job opportunities or by a change in the makeup of the population. In such cases the population grows to several times its original size, utilities are cut off due to unpaid bills and the houses cannot be heated. This may then lead to any combustible floor coverings being taken up and burnt, and the buildings being run down until they reach their structural limits.![]()

![]()

examples: Cité Soleil, Miyashita park

© Bessenyei Krisztina

Survival with social assistance

The “heated street” is the lowest level of provision for the homeless. In an article by Nóra Somlyódy in Magyar Narancs the director, Gábor Iványi, lays out the basic ground rules: “The heated street works according to the rules of the street. What is prohibited there is prohibited here. Robbing or beating people, or urinating on the walls is not allowed. You can withdraw here. You can’t bring a drink in, but you can come in drunk”. As he puts it: “A person who wants to live, who wants to be part of the community will want to be where life is being lived to the full. Homelessness is not the same as being without a roof over your head, it is about lacking companionship. That is why the hostels in the outskirts don’t work, and that is what is good about Dankó”.![]()

![]()

When floods, tsunamis, hurricanes, or earthquakes strike many families lose their homes at a stroke. Temporary shelters can be provided most quickly in gymnasiums, sports halls, or the main halls of public buildings. Structures that partition families and provide private spaces for them can be made with frames of cardboard, wooden or cardboard tubes, and curtains. Roofless, tent-like rooms are also used for this purpose.![]()

![]()

More than 60 million people at any time are forced, by war, political persecution, hunger, or natural disasters to leave their homes and live far from them, most often in foreign countries. That is planned as short-term humanitarian aid very often lasts for many years, and refugees can live in camps for decades on end. The simplest buildings are made of local materials and frequently by the refugees themselves. The majority are made up of tents, but there are also sites composed of trailers or prefabs, which is more typical for disaster relief in wealthier countries.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Some of these settlements are planned, the result of central or local government decisions, with the participation of professional architects. The motivation may be housing the displaced residents when slums are cleared by force or the settlement of nomadic ethnic groups. ![]()

examples: Blikkiesdorp, FEMA prefab, Paper Log House, EPPS4,

© Gareth Kingdon / source: garethkingdon.photoshelter.com

The next step above the “heated street” (a place to warm up by day and refuge at night) is the level of temporary hostels, inhabited by people who are willing and able to support themselves. There are typically 2-6 beds per room, with communal bathrooms and kitchens on each story. People can be effectively helped to escape from homelessness not by improving the standard of the hostels but by providing council housing and housing benefit.![]()

![]()

A special group of the homeless live in temporary homes for mothers. Some of these are mothers of small children escaping from abusive relationships, others are pregnant teenagers or teenage mothers who do not have homes of their own, or who cannot stay with their families. The problems are varied, and so too are the solutions: shared flats, secret sheltered accommodation, homes for babies, secondary schools with specialist provision for teenage mothers, individual and family therapy, and adoption or foster care are all options.![]()

![]()

example: Shelter Home

© Iñaki Bergera / source: archdaily.com

2.2 billion of the Earth’s population are children (under 18 years old) 16 million of whom are orphans (7.7 million of them live in Africa, 60% as a result of the AIDS epidemic). 250 thousand of these 16 million are adopted every year, which is the best solution both for the children and for society. It is important that, where possible, adoption should take place early, and in natural, family-like circumstances—even if the members of the family are not related by blood.![]()

![]()

Globally, 50,000 children and 15,000 young adults live in SOS Children’s Villages. Currently on average 150 children live in each of the 450 villages, ten to a house, supervised by a “mother”. There are between 10 and 40 houses in each “village” along with schools and other public buildings. The “families” are of mixed age and sex, which makes them seem more like families.![]()

![]()

Fifty years ago children’s homes were the most usual solution to housing orphans. In their original form life in these institutions, formerly called orphanages did not resemble family life at all: they were single-sex institutions with large shared dormitories, strict rules, schedules, and hierarchies between the carers and the orphans, or indeed between age groups. In recent years children’s homes have become more family-like—typically mixed groups of ten children have their own communal area and kitchen/dining room, with 3-4 bedrooms.![]()

example: Soe Ker Tie

© Pasi Aalto / source: archdaily.com

The elderly tend to be very attached to their own homes, even when they find it difficult to live on their own. Home care can cater to this preference, where trained nurses, physiotherapists, and social workers provide care in the elderly person’s own home. A new alternative solution is a version of co-housing for the elderly, which involves pensioners living in terraced houses or closely spaced detached houses or bungalows. This facilitates bespoke care and ensures that communal facilities are within reach and accessible. There are even examples where younger residents are mixed in with the elderly.![]()

![]()

Traditional old people’s homes are hotel-like buildings that have single and double rooms with their own bathrooms. Dining takes place communally as long as the inhabitants are mobile enough. The staff is trained to provide various levels of care, including nursing bedridden patients.![]()

![]()

example: House for Elderly People

© Fernando Guerra / source: skyscrapercity.com

One hundred years ago it was typical for 20-30 patients to be cared for per ward, and several wards shared common bathrooms and toilets. Today wards usually accommodate 4-6 patients with one or more bathrooms per ward. Individual suites are not uncommon in private hospitals. It is also worth mentioning field hospitals, hospital trains, and hospital ships developed for use in wartime. These latter are also often used to deal with natural disasters.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

For most of the 20th Century people with mental health problems were universally housed in institutions, virtually irrespective of the type of illness they suffered from or the seriousness of their condition. It has become quite clear that this is not the right solution, and that everything possible should be done to integrate them into society. If this is not practicable then hospital care is required. The situation is similar in cases of alcoholism and drug addiction, although (voluntarily agreed) confinement may be unavoidable to allow addicts to “get back on the wagon”.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In the past, apart from in wartime, people typically came to the end of their lives at home, not in a hospital. Advances in medical science have greatly extended average life spans, often without regard to human dignity. Hospice care is a relatively new field, which deals with patients in the lasts stages of terminal illnesses, often cancers, by alleviating their pain and preparing them to meet their deaths. Home-based care is desirable, but where this is not possible it should be provided in institutional settings where the patients can prepare for the unavoidable in the knowledge that they will go out with dignity.![]()

examples: Children’s Center, Helsingor Psychiatric Hospital, Surgical Field Hospital

© Daici Ano / source: archdaily.com

Not all religious groups build monasteries, only Roman and Greek Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Hindu, Buddhist, Taoist, and Shintoist monks and nuns live in monasteries, nunneries, chapterhouses, and abbeys. Of these, some spend all their time meditating while others also work (including nursing and teaching). All monastic buildings are characterised by the moderate lifestyles of the residents and strictly timetabled activities, as are the solitary dwellings of hermits. ![]()

![]()

![]()

On the “El Camino” route between Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port and Santiago de Compostela 190 hostels cater to the devoted Catholic pilgrims who walk it. There are many types of accommodation, from mountain shelters to hotels (Albergue, Casa Rural, Hostal, Hotel, Refugio, Cobertizo, Campamento, Acogida), and may be privately-, state-, organization- or church-owned (Asociación, Municipal, Parroquial, Particular, Cofradía, Monasterio, Privado, Benedictines, Xunta). Some rooms are available at set rates while others only request a donation (3-20 €, pago, donativo). Pilgrims may sleep in single or double rooms or in dormitories, and all the accommodation is simple and functional. According to seasoned pilgrims, there are, however, differences between the various places to stay: the church-run hostels are friendlier, cheaper, and give larger portions of food!![]()

![]()

The most important pilgrimage site among the eastern faiths is Mecca. In 2011 1,828,195 Muslims arrived there from abroad, while the number from Saudi Arabia was 1,099,522 making almost 3 million in total. The pilgrimage lasts two days, and most of the pilgrims stay in the tent city at Mina. The number of visitors is constantly growing and has increased thirty-fold in the last one hundred years, doubling in the last ten years.![]()

examples: Tautra Mariakloster, Wat Khao Buddhakodom, Mina Tent City

© Ammar Awad – Reuters / source: whatthefocus.wordpress.com

Dormitories (or halls of residence) for students have changed a great deal in the last hundred years. The traditionally strictly functional arrangements (dormitories or bedrooms, bathrooms, dining room, study room) have given way to apartment-like accommodation for 2-4 students with their own bathrooms. The change came about as a result of the recognition of the requirements for privacy and personal space of individuals and small groups and the creation of space to meet these needs.![]()

![]()

Youth hostels developed from the cheap accommodation for young people promoted by the Jugendherberge movement starting in 1912, and they continue to evolve today. The numerous varieties have one point in common, the dormitory, either mixed or segregated by sex, where young people sleep and socialize, usually on bunk beds. Almost all hostels have common rooms for cooking, eating, and meeting other young folks, and many also have hotel-type rooms at a higher rate. In many countries, these youth hostels function as student halls during term time and tourist accommodation in the summer, but this is by no means universal.![]()

Communal dwellings may also emerge spontaneously, when university students rent a house or flat together, organizing the living arrangements and dividing the rent. This may also be more officially organized, when an educational institution (or a related body) sets up and operates a network of shared student houses. This kind of accommodation may sometimes be bought as well as rented.![]()

example: Tietgenkollegiet

© Jens Lindhe, Lundgaard & Tranberg / source: ltarkitekter.dk

The era of the worker’s hostel was and is closely connected with the rise of the heavy and the manufacturing industry and the decline in the importance of agriculture as a sector of the economy. The ever-increasing numbers of workers in factories and on building sites needed to be provided with somewhere to stay. It is a transitional phase, long since past in the West, on the way out in Eastern Europe and on the rise in China. The buildings are, with a few exceptions, of a low standard, similar to basic hotels or low-quality youth hostels with minimal amenities.![]()

For shorter jobs, or for the early phases of large construction projects, mobile workers’ settlements were developed. The most widespread form of these is accommodation based on shipping containers, but trailers/mobile homes and prefabricated houses are quite common forms too, particularly in North America. Camps for researchers into geology, climate, botany, and fauna are similar in construction, often employing a mixture of intermodal containers and tent based systems.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

There are more than 570 oil and gas drilling platforms in the North Sea, and even without knowing how many workers live on these “oil rigs” the extreme conditions they operate under are grounds to include them in a list of extraordinary workplaces. On smaller platforms, the accommodation is made of converted shipping containers, while on larger ones, such as the Oseberg Field Center the living and working spaces resemble conventional land-based buildings. ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

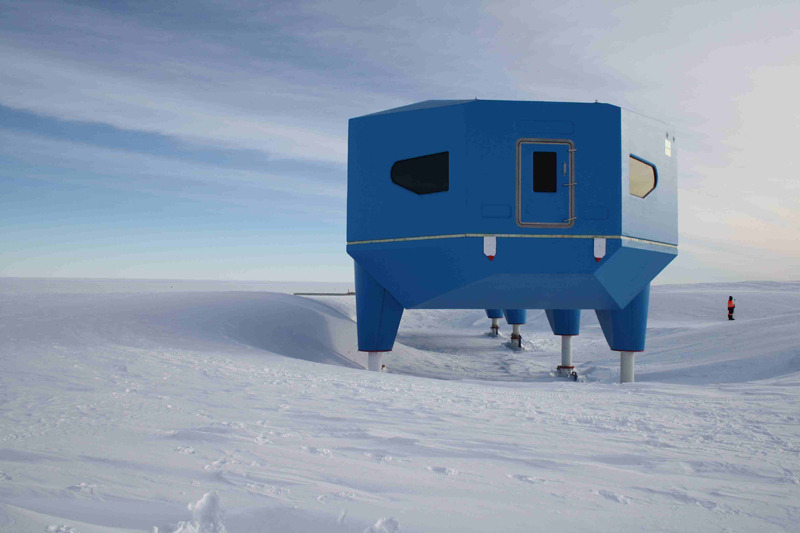

Antarctica, the region with the coldest climate on Earth, hosts four thousand researchers in summer and one thousand in winter. Techniques of construction, maintenance, and the management of life in the polar regions have been continuously improved since the 1950s, always on the basis of experience garnered on the bases inhabited at the time. The most important issues are pre-fabrication, transport by water and air, on-site assembly, and the creation of a habitable living environment. Other considerations would not have occurred to earlier designers of these bases: mobility both horizontally and vertically. Research stations that are sited close to the edge of the ice sheet are at risk of drifting off into the ocean as the ice sheet breaks up, while the constant heavy snowfall tends to bury structures within a couple of years. The latest research station, Halley VI, has solutions to all these problems—at least, it appears to have for the time being.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

examples: Foxconn worker dormitories, Halley VI

© antarctica.ac.uk / source: antarctica.ac.uk

There are many kinds of “tent cities” or tent settlements, including general-purpose campsites for tourists, summer camps on various themes such as environmental protection, horse riding, fishing, survival, scout or sports camps, and finally camp grounds at music festivals, where hundreds of thousands of people or even half a million may temporarily live under canvas, as at Woodstock in times of yore. The tents are usually either small, for 1-2 or medium-sized, for 4-6 people, and come in all shapes and sizes. Many are purely places for sleeping in, but others are also used for cooking, dining, or socialising and may be split into several rooms and semi-open areas. Some tents are put up in conjunction with cars or mobile homes, while others pop out of the roofs of camper vans.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

A mountain climbers’ base camp looks as if a dwelling has been built with all its rooms far away from each other. The climbers sleep, cook, eat, store things, bathe, and go to the toilet in separate tents. Climbers can spend several weeks on end in such camps, training, acclimatizing, and waiting for favourable weather conditions for an ascent. On smaller expeditions, the camps are simpler, with climbers sleeping and storing their gear in the same tent, where they might also cook and eat, doing the other daily activities somewhere else, or not at all.![]()

![]()

![]()

Caravans (or travel trailers) can be a place to spend a night, a summer, or a longer period of time. They can stand on their own out in the wilds or on a campsite among hundreds of others. One of the most popular types is the small teardrop-shaped travel trailer, the interior of which is solely for sleeping, with a place for cooking accessible from the outside. The medium-sized (5-7 meters long), or especially the larger type trailers (7-12 meters long) tend to have all the comforts of home nowadays: heating, gas cooker, water reservoir, sink, washbasin, shower, and toilet come as standard. These are utterly different from the single common ancestor of them all, which fortunately can still be seen today—the highly decorated Vardo (gypsy wagon of the British Isles) which was a traditional horse-drawn dwelling of the Romanichalok (nomadic gypsies in the British Isles). ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Ever since the invention of the reclining or fold back car seat it has been possible to get a short and usually not very good night’s sleep parked up at the side of the road in the car. In 1950 things changed with the launch of the Westfalia Campers based on the Volkswagen Type 2 (Transporter), which was the first mass-produced passenger van and marked the beginning of a new era. The minibus was such a success that it was only in the mid-1980s that French, American, and Japanese models were able to rival it. The original type has been continuously developed over the last six decades, but variants with opening roofs and built-in tent expansions date back to the 1950s.![]()

![]()

![]()

Camper vans are known outside of America, but a much wider variety of Recreational Vehicles (as they are known in the USA) is available there than in Europe. In America motorhomes or RVs are divided into three classes: Class A is based on a truck chassis with a customised living area built onto the standard driver’s cab and is typically about the size and shape of buses. Class B campervans are based on vans with heightened roofs. Class C motorhomes are built on truck chassis, with the living area behind and above the driver’s cab. The sides of some class A motorhomes can be extended outwards then retracted for travel.![]()

![]()

examples: JakPak, Tentsile, Airstream, Unimog U4000

© Samuelson Wylie Associates

Motels (Motor Hotel) date from the 1920s and owe their existence to the large-scale extension of the road network in the USA. They provide simple, usually cheap accommodation by the side of the road and may have one or more stories arranged on an I, L or U shaped floor plan. The rooms can be accessed directly from the guests’ cars. From the 1970s they faced increasing competition from better appointed mid-class (chain) hotels, which offered more facilities. The decline of the motel was hastened by the construction of new motorways which followed different routes from the older highways. It is a sign of the times that in 2000 the American Hotel-Motel Association changed its name to the American Hotel and Lodging Association.![]()

Inns, guest houses and tourist cottages are smaller, generally, family-run forms of accommodation for visitors and travelers. They may be interesting due to their age, with some Inns in Western Europe dating from the Middle Ages or the Renaissance, or due to their extraordinary natural surroundings, (e.g. mountain shelters and cottages in the Alps) or due to the special architectural concepts which inspire their design, such as the Tree Hotel in Sweden.![]()

![]()

It is in the interests of the hotel industry that every hotel meets the expectations of their guests, and for this reason, the standard of service provided by a hotel is defined by a set of regulations. The hoteliers, for their part, want their establishments to be fully booked before the competition is, so they constantly strive to make them more attractive to visitors. This led to creation from the 1980s onwards of boutique hotels, with a maximum of 150 rooms, but typically much fewer, where a cosy, friendly and individual atmosphere is the main attraction.![]()

![]()

Hotels have to compete for guests and to find customers who have specific demands so that they can find their niche. Boutique Hotels and Design Hotels operate like normal hotels but have a touch of individuality. Those who want something even more unusual can opt for hotels in converted bunkers, lighthouses, prisons, railway stations or boats, or can stay in underwater hotels or in a Japanese capsule hotel. This latter type is not a tourist gimmick, but an accepted part of the local culture.![]()

examples: Treehotel, 9h Capsule Hotel, Neue Monte Rosa Hütte

© Akihiro Yoshida – Nacasa&Partners / source: supertacular.com

There are two main types of sleeper bus, one kind is used by American and European musicians on tour while the other is used for long-distance travel in the Far East. The musicians’ double-decker coaches accommodate 8-12 people in comfort, with a range of amenities. Sleeper buses in India, China, and Vietnam tend to fit in as many sleeping places as a bus normally has seats, so, for example, 36 passengers can sleep during the 12-14 hour journey from Mumbai to Ahmadabad.![]()

![]()

![]()

There are various types of railway sleeper compartments including the traditional 4-6 berth sleeper compartment, the Couchette with reclining bed-seats, the two-person Twinette, and the one berth Roomette. Combinations of these types of compartments are used to best fill the available room in one or two-level sleeper cars of varying gauges, which can result in some interesting uses of space. The sleeping organization of sleeping cars can also be much simpler, with the most common arrangement in Asia ranging berths two or three levels high along either side of a central corridor to accommodate 72 (or in other classes 81) sleeping passengers.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Even as recently as two decades ago Soldiers in many countries typically traveled in railway cattle wagons when on exercises (The board on the side of the wagon read: 4 head of cattle or 10 pigs or 20 people). In the middle of the wagon was an empty area with an iron stove, with bunks along the whole width of the wagon in front and behind it, 10 soldiers sleeping at each end. The journeys did not last more than one day.

After the Second World War Hungarian prisoners were deported to the Soviet Union by rail, 35-60 per wagon, with a hole cut in the middle of the floor as the toilet, no heating, and journeys of 2-3 weeks.

The trains used in the holocaust were supposed to carry an average of 90 prisoners per wagon on a 4-5 day journey. However, the regulations were not always followed, as on August 18th 1940, when 45 wagons arriving at Belzec brought 6700 people, 1450 of whom had died on the journey.![]()

example: Amtrak Superliner II

© DaveLeritz / source: flickr.com

The Second World War gave a great boost to aircraft development, so much so that the ocean liner, which was at the time the leading form of intercontinental passenger transport, was to become marginalized within two decades. One of the largest of these ships in the middle of the 20th Century was the Queen Mary, which was 311 meters long, with 12 decks, a crew of 1101, and 2139 passengers (or in wartime 15,000 troops!). In the 1970s it was re-purposed, and today it is a floating hotel, museum, and conference center. Most ocean liners were either scrapped or converted into cruise ships, as riverboats had been decades earlier.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Yachts typically fall into two main types, sail- and motor powered, but this field is also becoming aware of the need for energy efficiency, and it is likely that in the future hybrid propulsion (diesel, solar, and sail) will become widespread. Sporting craft forms a minority, and most yachts are 10-15 man luxury leisure vessels. A useful indicator is the cost/berth ratio: for the highest class sailing yachts, this can be $1-5 million, for luxury motor yachts it ranges from 3-8 million dollars. In Hungarian terms, this is 0.2 – 1.6 billion forints/person.![]()

![]()

![]()

Naval vessels, especially aircraft carriers incorporate a large number of advanced technologies. While their interiors may also be interesting from an architectural perspective, as dwellings they are large rather than extraordinary. The US Navy’s Nimitz class aircraft carriers carry 85 aircraft supported by an air wing of 2480 and a ship’s company of 3200. Submarines typically have crews from 40 to around 100 for nuclear-powered vessels. In comparison with these vessels’ missiles, nuclear power plants, and systems providing oxygen and drinking water, the sailors’ bunk beds are rather less exciting.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

examples: Ady Gil, HMS Astute S119

© Earth Race / source: liveyachting.com

There are two main types of airships, not including transitional types: rigid framed airships, such as Zeppelins and non-rigid airships, or blimps. The form of the latter type is maintained by the pressure of the gas they hold, so they can only carry passengers and equipment in gondolas suspended beneath them. Zeppelins transported 90 passengers in living quarters in the base of their bodies, which also housed the crew. The airship was steered from its gondola. The passenger-carrying careers of airships came to an end in the lead up to the Second World War. By then the Germans saw more potential in airplanes, a view which was reinforced when, in 1937, the Hindenburg caught fire when landing in America and was consumed within seconds.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The definition of Air Force One is the airplane which the US president is currently flying on. Since 1990 the airplane used for this role has been the custom-designed three-level Boeing VC-25. The president’s suite occupies 370 square meters on board, including his sleeping quarters, office, conference room, guest rooms, medical bay, secret service quarters, kitchen, and large amounts of storage space. The private planes of the world’s wealthiest businessmen are comparable, Saudi prince Al-Waleed bin Talal bin Abdul Aziz al-Saud spent $450 million on a customized Airbus A380. The airplane was due to enter his fleet in 2013, alongside a customised BAe 125, an Airbus A320 and a Boeing 747. The good news for the middle class is that one can also sleep on some Singapore Airlines flights, even on double beds!![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Life on a space station is completely different to life on Earth, or indeed to how you would initially imagine it to be. The Earth is not a tiny speck floating in a void of darkness, the station is only five percent higher than the centre of the Earth, and the Earth does not float but streams past the astronauts head 16 times a day. The way of life onboard is a fascinating combination of the unimaginable and the down-to-earth, mostly due to the effects of weightlessness. Space stations and spacecraft are dwellings too: on journeys lasting several days or weeks, the astronauts must eat, sleep, groom themselves and do all the other things which they do on Earth. Spacesuits form a particular borderline case, as they are designed to be inhabited for a whole night, including sleep, although this capability has yet to be exploited in practice.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

example: International Space Station

© NASA – Paolo Nespoli / source: spaceflight.nasa.gov

Experimentation – new forms of accommodation in unusual places or of unusual construction

Experimental dwellings which make use of existing buildings or structures

It has become fashionable to live in all kinds of buildings and engineered structures. The draw of lighthouses or military bunkers might be their intrinsic interest value, the attraction of well-located warehouses, factory buildings or docks could be their cheapness, department stores or churches can have excellent urban settings, while other structures and buildings might simply attract those with bizarre or grotesque tastes. Lofts (in the American sense of the word) are generally spacious and high up—except for those which attract buyers exactly because of their odd, cramped interiors.![]()

It might seem strange, but finding a suitable existing building and constructing another dwelling on top of or on the side of it, perhaps painting it green, moving in and then, of course, publicizing what you have done might all be worth it—for the sake of a good view, for example. Whether these parasites will catch on remains to be seen.![]()

The squatting movement began in earnest with the 1968 student protests. The mostly leftwing youths did not accept the sanctity of private property: if buildings were left empty, and people had nowhere to live, then why shouldn’t they move in? Houses occupied in this way are not ruined but neither do they tend to be adapted or improved, which may be explained by the temporary nature of the occupation and/or by the lack of financial means to do so. Squatting is fundamentally a communal, social movement, so it is unsurprising that it often goes hand in hand with lifestyles such as communes and co-housing.![]()

Examples: Morton Loft, Parasite Las Palmas, Poortgebouw

© Daniel Nicolas / source: kortekniestuhlmacher.nl

Experimental homes on water or land

Houseboats are usually made by converting an old boat hull into a dwelling, while float houses tend to be houses built on pontoons or rafts. Both types differ from yachts, which are primarily means of transport, and dwellings second. While houseboats have traditionally existed in large numbers in many parts of the world (15,000 people live in them in the UK), float houses are the product of contemporary architecture. The experimentally inclined Dutch have built a floating settlement of 72 apartments as well as a waterborne student dormitory made of shipping containers. On the shores of the Bronx in New York, there is a rather different building: a floating prison was built for 800 inmates at a cost of $161,000 000.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Early humans lived in caves, while dwellings scooped out of the earth became widespread in Tunisia and the Near East in Antiquity and Middle Ages, and some caves are still inhabited in parts of China. Significant settlements were built in the walls of canyons and escarpments in Mali and the southwest of the USA several hundred years ago. In Iceland houses built partly of earth are considered traditional, while houses with roofs covered with earth can be seen in Swedish and Norwegian open-air museums (skansens). In their various settings, all building techniques have advantages and disadvantages, but with the help of modern building materials and techniques, earth houses can be brightly lit, dry, and have a pleasant climate – without using much energy.![]()

![]()

Examples: Toke Houseboat, Villa Vals

© Contact Indenfor & Udenfor / source: floatliving.blogspot.com

One-offs and mass produced “goods”

The dimensions of a standard shipping container (606x244x259 cm, 12019x244x259 cm) do not automatically earmark it for a glittering architectural career, never mind one in residential architecture. That it has in fact been widely used is largely down to a few advantages it does possess: a strong and durable structure, a modular system, ease of transportation, and low cost: a used 20-foot container can be had for $ 1200. Shipping containers have formed the basis for pavilions, mobile offices, accommodation units, and student halls of residence and no doubt many other uses will be found for them. Their cramped internal spaces pose fewer problems than their high heat conductivity and poor insulation, the latter problem being quite hard to remedy, whereas the lack of space can be solved by attaching several containers together. It is worth noting that although 40 feet containers share similar proportions to a children’s room in the Unité d’Habitation, they are larger in all dimensions.![]()

![]()

![]()

Manufactured houses (a type of prefabricated house) were first marketed in the 1950s in the United States. They were originally aimed at workers who had little money and moved around with their jobs, and so were 8 feet wide (2.40 meters) lightweight structures that could be loaded onto the flatbed of a truck for transportation. Later, when transport vehicles developed further they grew to 10 feet in width (3 meters) and the ability to move them and set them up more than once was dropped, as there was no demand for it. The next stage in their development was the advent of modular buildings, where the house was made up of several prefabricated structures joined together.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Not all products go into mass production. Some remain prototypes due to the lack of a manufacturer willing to produce them, while others are only ever intended to be one-offs. An example of the former is the Sleepbox, a box that provides all that is required to get some sleep when one is forced to wait at the airport. An example of the second kind is a hotel made of concrete pipes called the dasparkhotel, of which in fact there are more than one, but only enough were made for a small plot, not to go into production. An example of a true one-off is the Egg House, which was designed and built by architecture students in Beijing, to prove that anyone is capable of making their own dwelling—and living in it.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Examples: Cité à Docks, dasparkhotel

© Vincent Fillon / source: openbuildings.com

ORGANIZATION

The dwellings which are included in the collection of examples are all extraordinary in some way. They may be extraordinary due to the climatic and other physical circumstances of their setting, or they may be extraordinary as a result of unusual demands which are made of them, demands which are not usually made of residential buildings.

It is unusual for a dwelling to be in a desert or underwater, but it is also unusual for it to be occupied by a mass of people, or perhaps their ruler. It is also unusual if there is very little space for a person, or if it is occupied only for a day, or if it flies on a course around the world or if living in it means death.

The next section organizes the examples according to eight different criteria. For each situation typical and atypical responses are presented. Some dwellings may be unusual from more than one point of view.

Climatic conditions

The vast majority of houses are built in places where the climate is favourable to humans, and indeed to life itself. There are, of course, exceptions, and nowadays residences can be found all across the globe from the Polar Regions to the hottest deserts.

Ordinary: temperate (Continental, Oceanic, Mediterranean, Humid subtropical, Equatorial, Tropical Monsoon and Savannah climates)

Extraordinary: cold (Alpine, Polar and Subarctic climates) ![]()

Extraordinary: hot (Desert and Steppe climates) ![]()

Physical basis

Most dwellings are built directly upon the earth and further storey are built on top of the ground floor. Subterranean dwellings have existed since Antiquity, later floating houses appeared and today dwellings can be found in flying objects.

Ordinary: On the earth or on top of other built structures.

Extraordinary: In the earth or partially in the Earth ![]()

Extraordinary: On water and underwater ![]()

Extraordinary: In the air and in space ![]()

The form of community of the inhabitants

The vast majority of humanity grows up and lives in family groups, in some cultures in extended family groups. As a result of employment, study, or other circumstances many people live entirely alone, or in communities where they even have to share their sleeping places with strangers.

Ordinary: In families, in extended families

Extraordinary: Alone ![]()

Extraordinary: In communities ![]()

Social class of the inhabitants

In societies, generally, the majority of the people work, and they constitute the broadly conceived middle classes. / Above and below them are those people who either no longer have to work, or who cannot find work.

Ordinary: Lower and Upper Middle class, Working Class

Extraordinary: Upper class ![]()

Extraordinary: Underclass ![]()

Area per inhabitant

The various rooms in a dwelling are generally large enough for the inhabitants to comfortably perform the particular functions and activities practised in that society without inconveniencing other inhabitants or interfering with other functions. / There are places that are unsuitable to perform these functions, and there are demands on dwellings and rooms which are much greater than the norm.

Ordinary: medium relative area

Extraordinary: small amount of personal space ![]()

Extraordinary: a large amount of personal space ![]()

Degree of mobility of the dwelling

Most habitations do not move and cannot be moved, nor can they be taken apart and put back together again. / But there are nomads who live in tents, holidaymakers who stay in caravans and even astronauts…

Ordinary: Immobile in one piece or disassembled

Extraordinary: Mobile in disassembled form ![]()

Extraordinary: Mobile, but not habitable while moving ![]()

Extraordinary: Vehicles, in which you can sleep while traveling ![]()

Intended Usage

The majority of dwellings are, with various modifications, used for the purpose and in the way they were intended. / There are, however, dwelling places where even with the best will in the world one cannot say that they are being used as intended.

Ordinary: Buildings that are or were inhabited as planned by the designers.

Extraordinary: Not inhabited as originally intended ![]()