V 14 |

Low German Hallhouse |

type |

|

place |

|

population |

In medieval hall-houses one large communal space was shared by people, horses, cows and poultry. Living in such byre-houses seemed perfectly natural, as the warmth of the animals helped the residents get through the winter.

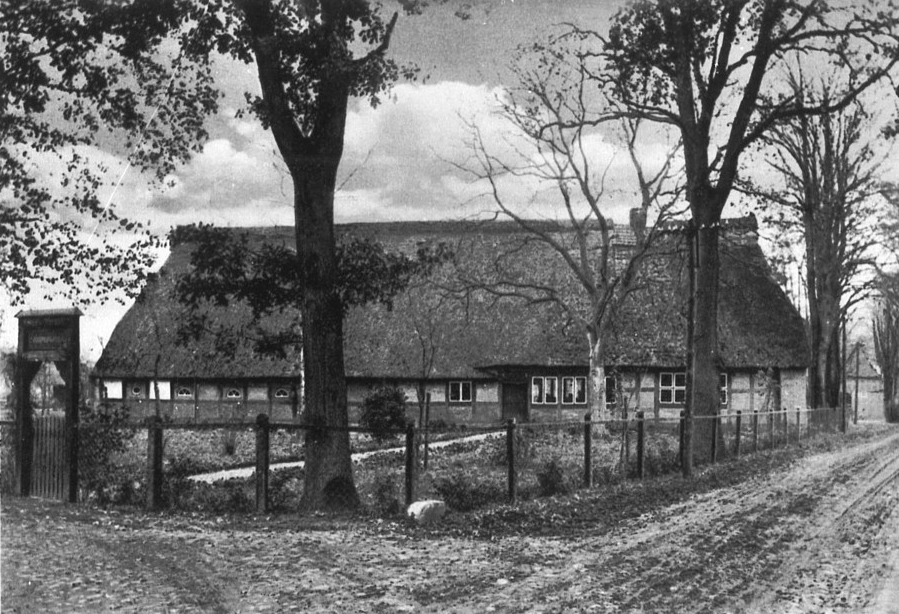

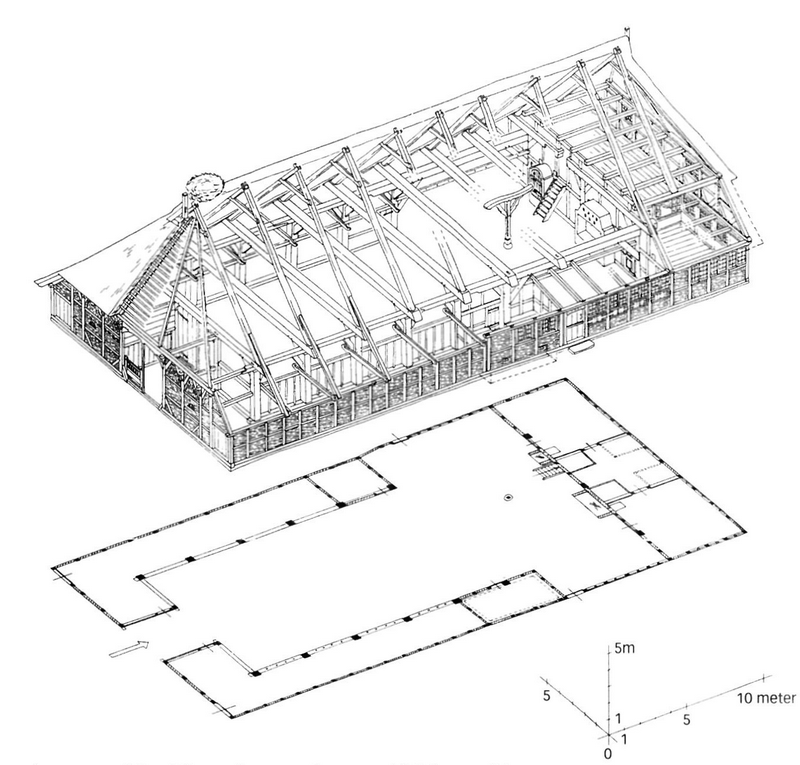

With the passage of time the interior became differentiated, and 500 years ago the Zweiständerhaus type of house emerged. It takes its name from the two rows oak posts running along the length of the long (usually 12×24 metres) pitched roofed building. The roof was thatched with rye straw and the exterior and interior walls were formed of a dense timber framework filled in with willow wickerwork and clay (wattle and daub). The building’s main gate was large enough to drive a well-loaded cart through, into a space between the stalls. In this area, the Diele (threshing floor) the hay could be loaded into the hayloft and it was the place where crops were processed, as well as being a place for celebrations or for laying out the dead.

Beyond the Diele was the Flett, a space for cooking over an open fire, and smoking meat and hanging hams from the roof beams. This fire heated the whole house, but even so in winter it was no more than 10-12 degrees Celsius, even with the animals inside to provide extra warmth.

From the 18th century the pace of change increased and a larger and higher type of house, the Vierständerhaus, with four rows of posts. The original oak was often replaced with pine and the open fire was supplanted by proper built-up hearths or stoves with chimneys while separate sleeping quarters were provided and beds, instead of the earlier sleeping bays (Schlafkammer).

Hall-houses were built right up to the end of the nineteenth century, and in poorer regions many still remain to this day. A type of circular village layout found in the German-Slav borderlands, the Rundling is also made up of hall-houses, originally five of them arrayed in a semi-circle and later the large farmsteads were divided into 2,3 or 4 wedges and more houses built to form a full circle.